Darwinism and the Price of Money

“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happen.”

Vladimir Lenin

Federal Stimulus

The common narrative regarding efforts to contain financial damage from the Covid-19 pandemic has been dominated by the unprecedented (both in speed and magnitude) fiscal and monetary stimulus from the US Treasury and Federal Reserve. The $2.3T CARES Act and $2.6T+ capacity of Section 13(3) Federal Reserve authorized lending facilities (including reincarnations of 2009’s alphabet soup of TALF, CPFF, PDCF, and including other new ones such as MSLP and PPPLF) alone combine for ~$5T of federal stimulus, and does not even yet include a “Phase 4” program which is expected to be approved by Congress in 3Q20.

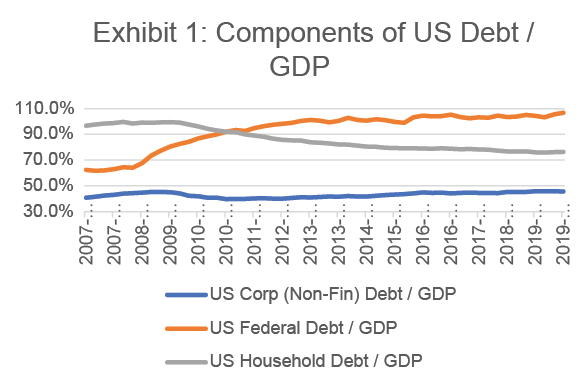

While there is no doubt that government assistance for pandemic economic relief was required, one possible unintended consequence of the scale of Fed intervention may be a distortion of the normalized functioning of private sector capital markets. Although there had been intermittent efforts to reduce quantitative easing after 2009, those efforts never really gained momentum, as the economic GDP recovery had been quite slow.1 On top of continued budget deficits throughout the 2010’s, the US entered 2020 with a Fed balance sheet that had steadily crept up to quadruple with in excess of $4T in holdings (from less than $1T pre-GFC).2 (See Exhibit 1 for comparison of separate components of overall US debt as % of GDP from 2007-2019; source data: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/). As Covid has caused substantial economic damage through both supply and demand shocks beginning early-March, the Fed’s balance sheet has almost doubled in less than 3 months to over $7T, with some predictions of an increased Fed balance sheet up to $10T by end of 2020. The combined effect of significant fiscal and monetary stimulus and yield curve control all have helped to retain extremely low interest rates, in order to continue to ease credit flow to support the economy as it recovers, which in turn supports asset valuations throughout the risk spectrum (debt to equity).

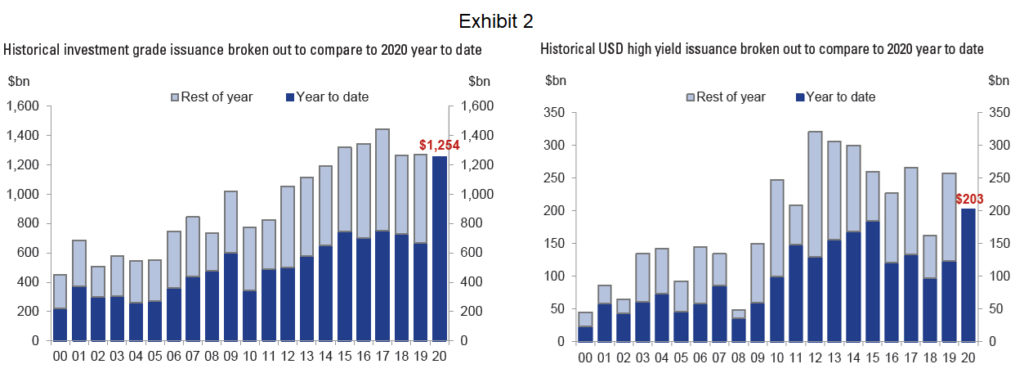

As one example of the effects of the Fed’s explicit and implicit balance sheet support, US private sector companies have opportunistically issued a record amount of bonds year-to-date in the primary investment grade and high yield markets. (See Exhibit 2; source data: Dealogic, Goldman Sachs; data as of 6-25-20).

Normalized private sector capital markets function properly through allocating capital on a risk-adjusted return basis. This necessitates, by definition, a Darwinistic process of differentiating between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’—less capital availability correlates with riskier and/or less ‘deserving’ recipients, thus ensuring that the most creditworthy recipients have capital accessibility. Even pre-Covid, the increasing magnitude of the Fed’s efforts may have mitigated the ability of the private sector markets to properly function. Now that we are in the “new normal”, accurate private sector capital pricing signals may have been even more dampened as the Fed has been forced to intervene even more. Federal stimulus is a blunt tool, as opposed to a precision instrument. Over a longer-term period of time, this may result in the continued funding of companies which would typically not be funded during a period of normalized capital markets functioning. Only time will tell.

SMB Financing

We turn now from the macroeconomic ‘top-down’ perspective to one of the key ‘bottoms-up’ barometers of economic health, small-medium business (“SMB”–generally defined as <500 employees) financing, one which may not have benefitted as much proportionally from the federal stimulus. More than 99% of US firms employ <500 people, while altogether, those SMBs account for almost ½ of private-sector jobs.3 Here we look at the relative benefits of federal intervention (as opposed to the overall macro effect)—while stimulus has benefitted capital market participants on the whole, resulting capital accessibility may not have been proportionally equal.

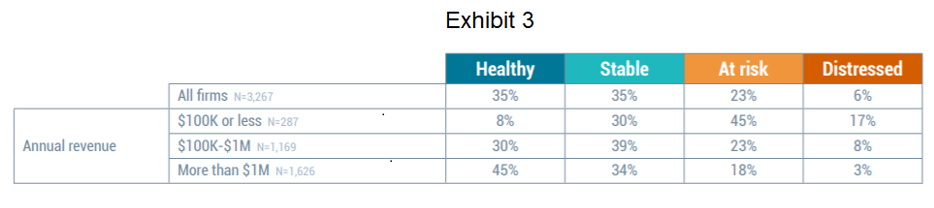

SMBs are particularly prevalent in service industries and include examples such as auto repair, restaurants, barber shops, and home repair contractors. Due to the nature of the sectors in which SMBs are prevalent, they are especially affected by ‘social distancing’ measures. For example, SMBs constitute approximately 60% of employment in the hospitality and leisure sector.4 As shown in Exhibit 3, SMBs have thus been identified as particularly vulnerable to the economic effects of Covid.5

In a hypothetical utopia, the economy and capital markets would be best served by measuring the exact Covid impact on each company participating in the economy, and providing exactly that amount of restitution through federal stimulus, no more, no less, to those companies. Since that utopia is impossible, federal stimulus does the best job possible in allocating for Covid impacts while attempting to disturb capital markets functioning the least. Nonetheless, while federal stimulus to aid SMBs has included ~$700B in PPP loans/grants, it is possible that, given SMBs account for almost ½ of private-sector jobs, when compared to the $2.6T+ targeted to larger companies (almost 4x the magnitude of the PPP program), this amount of aid may end up to be less helpful (on a relative basis).

Current Transactions

In the course of our many discussions regarding capital investment transactions over the past few months, we have noted a high degree of uncertainty regarding finance companies’ capital needs. Due to a combination of consumer and commercial forbearances, fiscal and monetary stimulus and unclear pricing signals from the available data, it has been difficult to obtain a clear picture of companies’ true financing needs. We have underwritten quite a large number of financial asset portfolios and are in the process of transacting on a portion of those underwritten. Through our combination of capital, expertise, and experience with all types of financial assets, we look forward to helping to solve any finance company’s liquidity concerns.

Footnotes

- https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ES_20190430_Baily_Productivity_Slides.pdf

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/20200612_mprfullreport.pdf, pg. 24

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/20200612_mprfullreport.pdf

- https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/FedSmallBusiness/files/2020/covid-brief